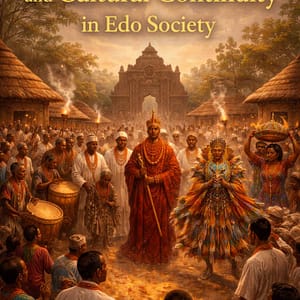

This article examines festivals in Edo society as vital cultural institutions through which history, memory, and identity are preserved and transmitted across generations. It argues that Edo festivals are not merely celebratory events but structured systems of ritual practice that function as living archives, embedding historical narratives, spiritual beliefs, and moral values into communal life. Through repeated performance, festivals sustain a cyclical understanding of time in which the past is continually renewed in the present.

The study explores major Edo festivals, including royal, ancestral, agricultural, guild, women’s, and masquerade festivals, highlighting their roles in reinforcing kingship, social hierarchy, moral order, and communal cohesion. It demonstrates how ritual power, embodied performance, music, symbolism, and spatial organization work together to transmit cultural knowledge beyond written records. Festivals are shown to serve as mechanisms of education, governance, and social regulation, ensuring continuity through collective participation.

Finally, the article analyzes the impact of colonial disruption and modern influences on Edo festival life while emphasizing the resilience and adaptability of these traditions. Despite suppression and transformation, Edo festivals have survived through adaptation, revival, and intergenerational commitment. The article concludes that festivals remain central to Edo cultural continuity, serving as enduring bridges between ancestors, the living, and future generations in a rapidly changing world.

Avis

Il n’y a pas encore d’avis.